Raised BedsWhy Grow in Raised Beds?I love my raised beds and usually add 1 to 2 more every year to my garden. There are several advantages to using raised beds to grow vegetables.

MaterialsWhat materials to build your raised beds with is a hotly debated topic. I prefer untreated wood, although I would be comfortable using treated wood today as copper is used as a preservative rather than arsenic. A study by Oregon State University (4) has found that only one inch of soil along the edge of the bed shows increases in copper levels, and that increase was small (20 ppm over untreated raised beds). We started with untreated lumber as it was cheaper than treated and even using untreated 2x10 boards our raised beds have lasted about 7 years. We built our first raised beds in 2017 and only this year (2024) have we started to replace some of the sides. We bought an Alaskan sawmill this spring and own a red pine plantation that needs thinning, so my husband has been milling 6x6s to build new raised beds and replace our older raised beds. The big advantage of 6x6s is that you can more comfortably sit on the edge of the bed to plant or weed. The gold standard for raised beds is cedar wood. I would love raised beds made out of cedar 6x6s but cedar wood is unfortunately extremely expensive. If you are only going to build one or two raised beds you could consider cedar depending on your budget. However, I have 19 raised beds and the cost of cedar is unrealistic. There are also other rot-resistant wood types, such as redwood, but they can be hard to source and expensive. Metal-raised beds, usually steel galvanized with zinc to prevent rusting, are becoming more popular. Although zinc can be toxic in large amounts it seems unlikely that enough would leach into a raised bed to cause toxicity issues. We also use galvanized food and water containers for our chickens and ducks and galvanized water tanks for livestock have been used for a long time. Therefore, I feel a galvanized metal raised bed is unlikely to cause health issues. Furthermore, I have heard good things about some of the metal raised bed kits (such as Epic Gardening Birdies Metal Raised Garden Beds[6]) you can buy regarding longevity and ease of construction, but I have no experience with them myself. If you decide to buy a galvanized livestock tank to use as a raised bed instead of a raised bed kit, just be sure to add drainage holes and ensure it is tall enough to accommodate the roots of your plants. Concrete (cinder) blocks are often used because they are easily available, relatively cheap, and heavy so no extra supports are needed. I would not use concrete blocks because, in addition to cement, sand, and gravel they also contain fly ash which is a byproduct of burning coal. However, this will likely only leach into the soil in large amounts if the integrity of the block is compromised. If you use concrete blocks, in good condition, this may be an acceptable choice for a raised bed. You can also choose to line your concrete blocks with a food-safe plastic liner, however, many people do not like growing food in plastic, even food-safe plastic. Materials I do not recommend are railroad ties, due to the creosote used as a preservative which is also a carcinogen. I also see old tires being used locally as raised beds, but this is not recommended since tires are made of petroleum-based products. Rubber degrades with exposure to UV light from the sun which will then leach petroleum chemicals into your soil. SizeA typical raised bed size is often 4x8 feet. The first raised beds we ever built were five feet wide. This was too wide to easily reach the center of the bed for planting and weeding. I suggest limiting your raised beds to no more than four feet across, but three feet is also acceptable, particularly if you are on the short side. The distance in length does not matter although I suspect eight feet is often used because wood is readily available in eight-foot sections, and it is easier to transport. There is no reason however that you cannot make longer raised beds, you would just need support along the way. Many people also get creative and make raised beds in different shapes to make meandering pathways between them. I am unfortunately not that creative and line mine up in two rows with each bed running north-south. My older raised beds were made using 2x10s so they were roughly 9.25 inches high or, if we added two layers, for example, to grow asparagus with deep roots, were 18.5 inches high. These were a great height but made it difficult to sit on the edge given the sides were only 1.5 inches wide. Our new raised beds made with 6x6s are currently only one layer high, so 6 inches (these are actually 6 inches high since we milled them ourselves, if you buy 6x6s in a lumber yard they will likely be 5.5” unless you can find rough sawn wood). We plan to slowly add more layers of 6x6s as we have the time to mill more logs. Ideally, a raised bed is 12-18 inches tall, but I found having the wider 6x6s raised beds easier to work with than the taller 2-inch-wide boards so am willing to sacrifice height temporarily until we mill more 6x6s. Even a 6-inch raised bed provides advantages to growing directly in the ground. As far as spacing is concerned, I like 3-4 feet between each raised bed. I found that 2 feet is too small to easily work in between raised beds. Buy or Build?Whether you buy or build your raised beds comes down to two different factors: budget and DIY ability. We chose to build our raised beds because I wanted quite a few of them which made buying them too expensive, and my husband and I are reasonably handy. We already had the tools needed (saws, drills, etc.) to build wooden raised beds. If you do not already have tools available weigh the cost of buying a raised bed kit with the cost of buying or renting tools plus lumber to build your own. Many hardware stores will also cut lumber to size for you so that could eliminate the need to buy a saw. When we built our raised beds with 2x10s we used screws to hold the boards together with a 2x4 at the corners. When we used 6x6s we pre-drilled holes through the 6x6s and then pounded a long spike through to hold them in place. In general, screws are preferable to nails because if you make a mistake, you can easily remove the screw. One thing we did not add to our raised beds is hardware cloth lining the bottom. This is used to prevent rodents from burrowing underneath and eating the roots. This has not been a problem for us but if you have high rodent pressure in your area I would recommend it. SoilWhen starting a raised bed from scratch I like to combine peat moss (make sure you buy the sustainable Canadian peat moss), topsoil or garden soil (about 50%), compost/composted manure, and sometimes a little sand. We usually get our topsoil/garden soil delivered as it is cheaper than bags if you need large amounts. Our compost is either our own (kitchen scraps mixed with used pine shavings from our chickens and ducks that have been composted sufficiently to reduce any pathogen load) or compost in bags we get from our local home improvement store. Sometimes peat moss is not recommended because it can cause your bed to dry out too much. I add no more than half a bag to my 4x8 foot raised beds and have not had a problem. After a raised bed is established, I usually add an inch or two of compost each year to maintain the fertility of the soil. I also grow many plants in pots and when I need to refresh the soil in my pots, I often dump the leftover potting soil into my raised beds (assuming no diseases were present). Potting soil usually has good drainage so this can also increase the health of your raised bed soil. The cost of filling a raised bed can be as expensive or more expensive than the cost of a raised bed itself, so be sure to add up the total cost before you build too many raised beds you cannot afford to fill. This is why we have slowly added 1 or 2 raised beds per year rather than making them all at once. ConclusionI love raised bed gardening and firmly believe the advantages outweigh the time and cost required to build or buy them. The vegetables in my raised beds routinely outperform my other vegetables in both output and health. If you wish to learn more about raised bed gardening, I encourage you to read or listen to Joe Gardener’s blog/podcast (links below) which is very comprehensive, and check out the other resources provided. References and Resources

0 Comments

The Basics of Seed StartingI started growing my vegetable plants from seed rather than buying seedlings from big box stores or local greenhouses for several reasons. First, I love working with soil and plants so by starting seeds I get to start gardening (albeit indoors) earlier than I would if I bought seedlings. Second, I have a very large garden, so I save money by buying seeds and starting them rather than buying plants. Lastly, one of my favorite parts of having a garden is to try many different varieties of vegetables, especially tomatoes and peppers. If I buy my seedlings from big box stores or even independent greenhouses my selection is much more limited than if I buy seeds and start my own. Before I get into the supplies you will need to start seeds let's discuss timing. I see this question asked all the time in my online gardening groups and there is not a simple answer. The easiest way to get a rough idea of when to start your seeds is to first figure out your average last frost date in spring. There are lots of different websites and I would recommend checking several, but this one has worked well for me and gives dates close to many other sites. Once you enter your zip code, look for the 50% chance of last frost at 32°F, which for me is mid-May. Remember, this is an average and in any given year the date could easily fluctuate by a week or two. Realistically, I generally do not get my warm season crops, both directly sowed seeds and transplants, planted until the soil warms up more which is usually the first week of June for me. Once you know your average last frost date count back, however many weeks is recommended (check your seed packet or do an online search), to figure out when you need to start seeds. For slow-growing and slow-germinating seeds like onions, celery, artichokes, and some herbs like parsley I start seeds 8-10 weeks before my last average frost date. For many cold crops like cabbage, kale, broccoli, and cauliflower I plant 7-8 weeks ahead. For peppers which can take weeks to germinate (especially the super hots), even with a heat mat, I start about 7-8 weeks before my average frost date, but I generally plant them out 2 weeks after my last frost date since peppers do not like the cold. Lastly, for tomatoes, which germinate and grow more quickly than peppers I start later, about 4 weeks before my last frost date. Again, I usually wait a week or 2 after my last frost date to transplant to make sure the air temperature and soil temperature are warm enough. The reason seed starting dates is not an exact science is because even knowing your average last frost date you may live in an area with a microclimate that is either warmer or cooler than average. You can start tracking your temperatures where you live, but that would take years to get good data or learn to enjoy a little trial and error. As mentioned above the actual last frost date can vary because it is based on an average. Also, the temperature in which you are growing makes a difference. I found that when I started putting my seedlings into a greenhouse for a couple of weeks before I planted them, they grew much faster than when I had them growing in my cooler basement. So, I had to adjust my dates and start my seeds later to account for faster growth. The best resources I have found to help you calculate dates are from Johnny’s Selected Seeds which has SO MANY freely available calculators and tools, some of which are downloadable. My favorite tools are their seed-starting date calculator for seedlings and their fall-harvest planting calculator. They also have a succession-planting calculator which I have never used it as I do not have much time to replant most seeds due to my short growing season. Once you have your seeds organized and dates figured out it is time to get all the supplies you need. Some of these supplies are optional so buy what you can depending on your budget. I also recommend starting just a few different types of seeds in your first year and if it goes well increase the number you grow in the years after if you want. You do not want to end up overwhelmed or with a bunch of leggy, or even worse dead seedlings because things went wrong (trust me I’ve been there). Seedlings in 6-cell pots with a fan blowing (middle) to strengthen them and help avoid damping-off. SuppliesBefore you start seeds, you need to stock up on a few supplies.

From left to right, onion seedlings under 4 foot LED 5000K lights, lettuce seedlings potted up into 3.5 inch square pots, and endive and pac choi recently transplanted into a raised bed. ConclusionI love starting my own seeds and hopefully you will too. Just remember if it does not work out great your first time, try again! My first time I started seeds I went on vacation and the person who was checking in on my seedlings overwatered them because she thought they were dying. It turns out they were dying because I had problems with damping-off (this was not her fault, some had started dying before I even left for vacataion). Unfortunately, watering even more makes damping-off worse so I lost about half or more of my seedlings that year. I have since learned that less water is usually better and I also try to time my vacations until after the majority of my plants are in the ground! Good luck and feel free to contact me with any questions! Organic Pest Control: BtBt is Bacillus thuringiensis, a bacterium naturally found in the soil used to control pests, is the most widely used biopesticide worldwide (1). A biopesticide is a pesticide derived from a biologically occurring, natural source, such as from an animal, plant, bacteria, or mineral. Although the use of Bt can be traced back to the early 1900s the first commercial use was in France in 1938 (1, 2) and was first registered for use in the United States by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1961 (3). B. thuringiensis is a rod-shaped bacterium that switches between normal vegetative growth and a sporulation state in which round spores are formed (4). When spores are formed, the bacterium also produces crystalline proteins (Cry family of proteins) which are toxic to certain insects (5). When the insect ingests the Bt, for example, while eating a leaf sprayed with the Bt-containing pesticide, the crystalline proteins bind to specific receptors on the epithelial (skin) cells of the insect’s gut, the cry proteins then form a pore in the cell, causing them to lyse (rupture) due to osmotic shock (6). Other organisms, such as humans, other mammals, birds, earthworms, and most other insects do not have the receptor necessary for binding and are therefore not harmed (2, 3). Different subspecies of Bt are specific for different types of insects. For example, Bt kurstaki (Btk), the most common and easiest to find Bt, is used to control Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) larvae such as cabbage worms, cabbage loopers, gypsy moth, tobacco hornworm, and more (2). It has no effect on beneficial insects like honeybees or ladybugs (3) but should only be applied to plants that butterflies, such as monarchs, are unlikely to visit, for example, brassicas. Bt israelensis (Bti) is used to control mosquitos and fungus gnats (Dipterans or flies) by targeting the larvae of those insects (2) and is commercially available as Mosquito Bits or Mosquito Dunks. Mosquito Bits are in pellet form and can be sprinkled in standing water to kill mosquito larvae. I have also mixed the pellets into my plant water when I have a fungus gnat outbreak in the soil of my house plants. Simply watering your plants soaks the soil with the Bti allowing the pesticide to control the larval stage. Mosquito Dunks are larger and float on water and slowly release the Bt as they dissolve over time and can also be used in standing water. Bt aizawai (Bta) is used to control certain moth larvae species, especially those that eat grains (6). This formulation appears available for commercial farms but not for the average homeowner to purchase. Bt tenebrionis and Bt san diego are used to control beetles such as the Colorado potato beetle (6). This formulation also appears available for commercial farms but not for the average homeowner. AdvantagesBt is a very safe pesticide (2, 3) especially when compared to other non-organic synthetic pesticides and even some organic pesticides. Bt is also very effective against specific pests (6), but its mechanism of action does have some disadvantages (see below). Bt is also a very host-specific pesticide (2, 3, 6), particularly when used according to the label instructions, which reduces off-target effects. DisadvantagesBecause the larvae need to eat the Bt for it to be active, plants will sustain more damage until the toxin takes effect, usually within a few days. The Bt spores are also sensitive to UV light (sunlight will break them down) (7) and may wash off the leaves, particularly after a hard rain. The typical half-life of Bt on foilage in field conditions is 1-2 days (7), therefore it is recommended that plants be sprayed weekly or following a hard rain or overhead irrigation. There is also the possibility of off-target effects however, Bt is much more host-specific than many other pesticides on the market, even other biopesticides. When used carefully on specific plants off-target effects are minimized. ConclusionsOne last use for Bt has been introducing the gene into the plant itself, making a transgenic crop. This eliminates the need for spraying, instead, the plant cell itself produces the insecticidal protein. The use of Bt in transgenic crops is beyond the scope of this blog post and I will likely address the topic in the future. However, in the United States, the most common Bt crops are corn and cotton, but potato and tobacco have also been modified. To my knowledge these crops are not available to the average home gardener but only to commercial farms. References

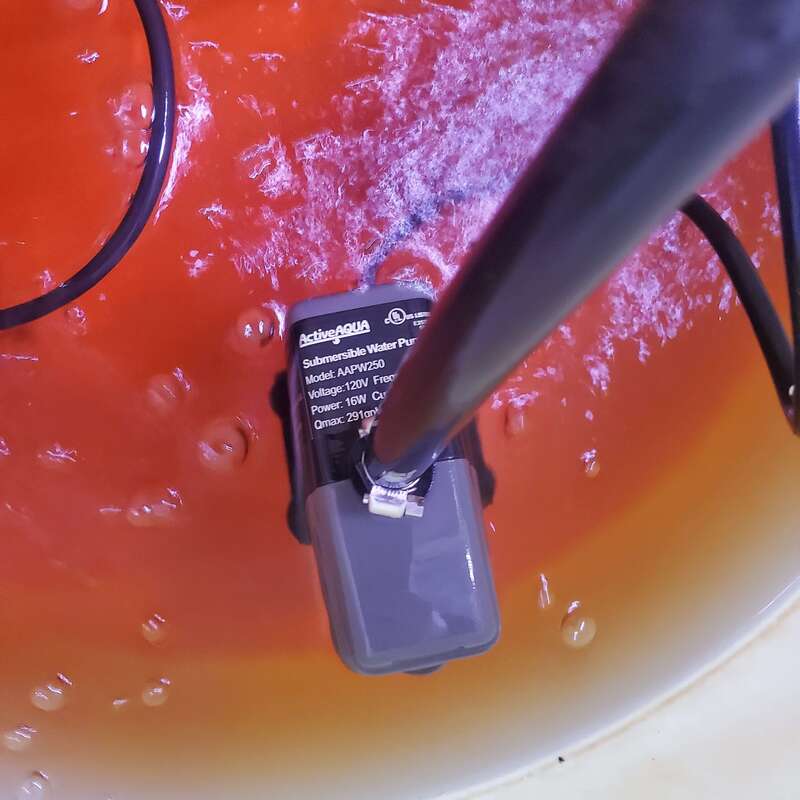

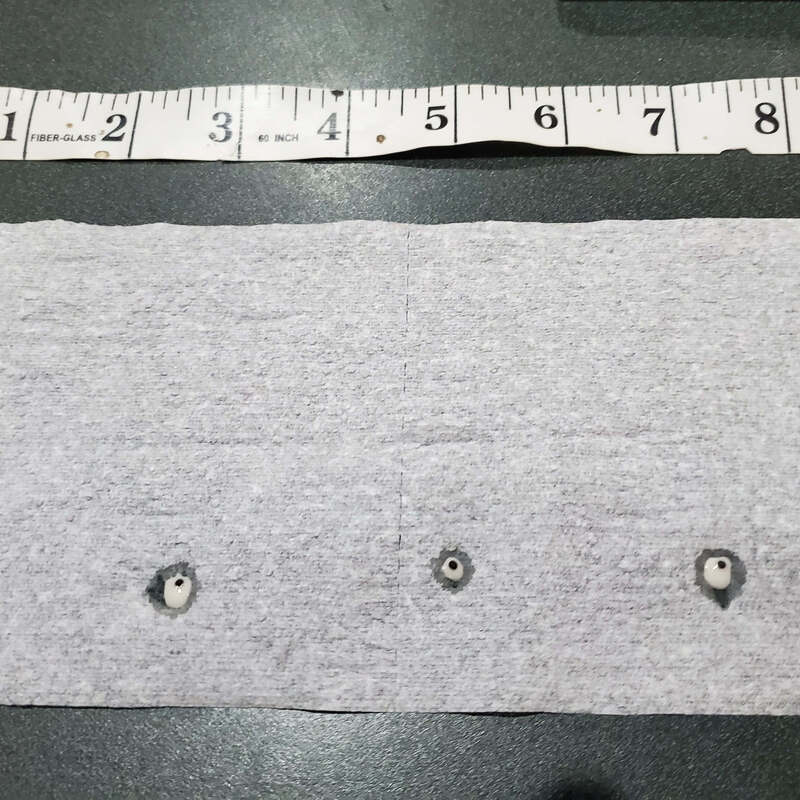

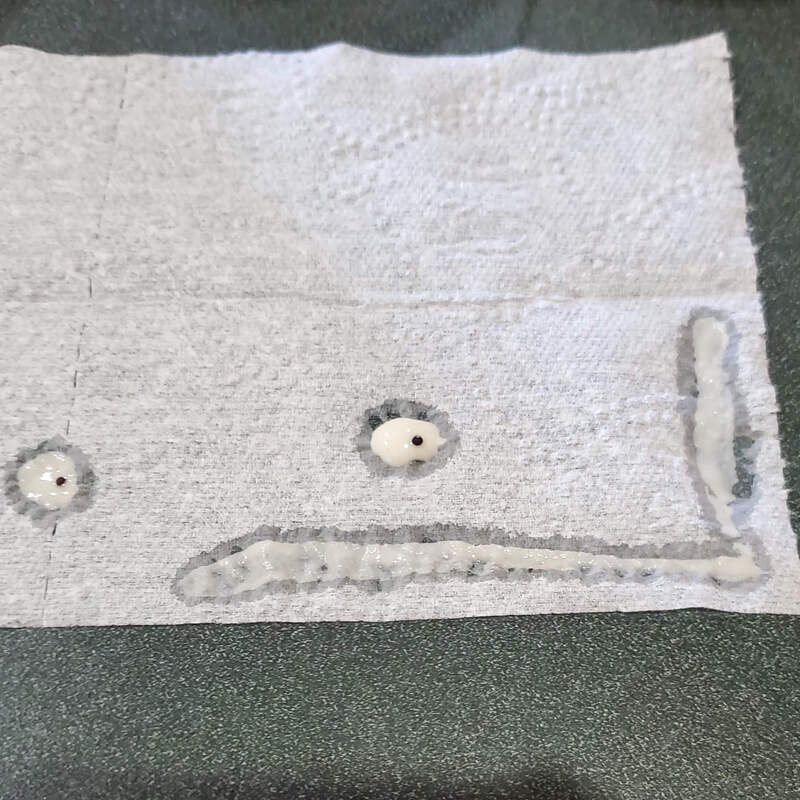

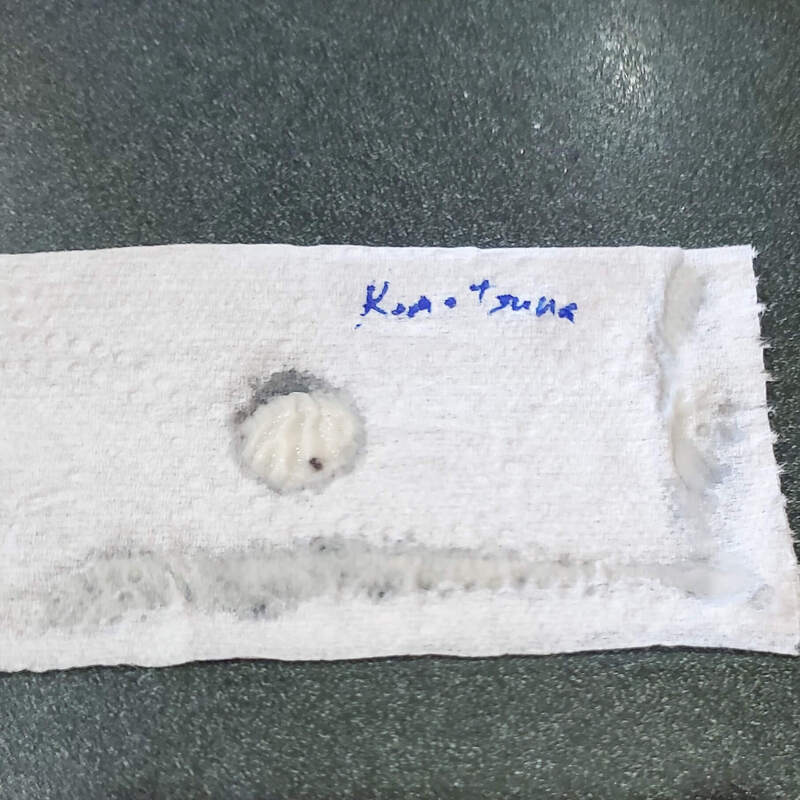

HydroponicsWhy Hydroponics?I have been interested in hydroponics since I was a child. For an elementary school science fair, I compared traditionally grown vegetables (beans and corn) to hydroponically grown ones. Although I did not win, which I am still a little sore about, I did learn the basics of hydroponics. The good news is that 30 years later there are many more options out there for hydroponic gardening. You can purchase a setup, or you can DIY one. You can use your setup indoors, in a greenhouse, or even outside. You can make up a nutrient solution from scratch or you can buy pre-made powder or concentrate and dilute it. You can use media-based hydroponics or no media at all. Or, for an extra challenge, you can venture into aeroponics or aquaponics. Although I like the idea of hydroponics, part of me feels like it is cheating without using soil. I love gardening, mostly because I can spend time outdoors and play in the dirt. Although some types of hydroponics use media, no hydroponics system uses actual soil. However, the big plus for me that outweighs all others is that hydroponics is a way to extend the season and harvest vegetables in the middle of winter. For this article, I will focus on an indoor system that uses supplemental lighting. I live in central Wisconsin in USDA agricultural zone 4b which means I can work in my garden from roughly April to November. We often still get snow in April, so it is not unusual for my cold crop seeds to get several inches or more of snow on them (they still sprout just fine though). We can also have a hard frost by mid-September although most years it is in October, but it has also been as late as November. I extend the season the best I can with frost covers but unless I buy a heated greenhouse there is not enough heat in a Wisconsin winter, or even enough light in a day to grow crops. Most plants do not grow much when days get shorter than 10 hours of light. When daylight falls below 10 hours per day, this is called the Persephone period, named after the Greek goddess of the harvest. For my area, that means that without supplemental light I cannot grow anything outdoors from November 5th to February 4th. You can however overwinter cold-hardy crops like spinach, kale, parsnips, and carrots. These crops will survive, but not actually grow until the daylight hours get longer, and the temperatures are above freezing again in the spring. What Type of Hydroponic System?Lately, Aerogarden and similar systems have become very popular. They are also very expensive. I did finally break down and buy a small Aerogarden on sale last year and I must admit it is great for crops like salad greens and herbs. I first tried tennis ball lettuce using one of the grow-your-own kits and it grew fantastically. You do not get much product, however, but it was enough for a couple of small salads or lettuce for sandwiches over the course of several weeks. However, what I am most interested in growing during a Wisconsin winter are tomatoes and peppers. I am obsessed with growing tomatoes and peppers because I love to try all the different varieties, and there are thousands of them out there. You can also easily save your own seed which means you do not need to keep buying fresh seed every few years. I discovered, however, that to grow larger crops with a purchased system is at least $800 or more. So, I decided (with the help of my husband) to build my own hydroponic system that can accommodate larger, flowering crops. Please note there are many, many different types of DIY hydroponic systems, I am only going to cover one as it is the only type I have experience with thus far. After extensive research, I realized the hydroponic system that is used most often for larger flowering crops is the Bato bucket or Dutch bucket system. Bato buckets are a type of ebb and flow (or flood and drain) system of hydroponics. These are not the easiest hydroponic systems to set up, but they are also not so complex that a reasonably handy person with a few common tools cannot do it either. There are two steps to the ebb and flow system, the flooding step where the nutrient solution floods over the roots, and then the drain step where the nutrient solution flows back to a reservoir. You can keep the Bato buckets (pots) separate or link them up in sequence to an irrigation system with a pump and drainage tube which allows them all to be fertilized at the same time and then have the nutrient solution drain back into a reservoir to be re-used during the next flood cycle. Another huge advantage to this system is that you can use timers to have not only the lights turn on and off but also turn on the pump which irrigates your buckets, without any labor on your part, once the system is set up. I have my system set to pump nutrient solution just three times per day (8 am, 2 pm, and 8 pm) for 30 minutes each. Because this type of system does not have nutrient solution flowing over your plant roots all the time, you need to use some type of media that holds moisture so the roots do not dry out in between irrigation times. The most common types of media used in hydroponics are perlite and expanded clay pebbles also known as LECA (light expanded clay aggregate, one common brand name is Hydroton). I have tried both and thus far prefer the expanded clay pebbles, but both have worked well for me. Perlite is made of volcanic rock and is cheaper than clay, but it can only be used 1-2 times before fresh is needed. I plan to add my used perlite to my raised beds outside to increase drainage, so I will not need to throw it out after it is used. Perlite is good because it is lightweight and retains water well, but I found it difficult to clean to reuse it. Additionally, because the pieces are small you need to use a mesh strainer bag in your buckets to keep the perlite from washing into the drainage system and clogging your pump. I used paint strainer bags, but I am uncertain if the plastic used in them is food-safe (if anyone knows send me a message!). Therefore, my preference is to use the expanded clay pebbles. Because the clay pebbles are bigger and will not clog the drainage system there is no need for the paint strainer bags, and in my opinion, less plastic is always good. Both the clay pebbles and perlite are dusty so be sure to wear a mask when using them until the substrate is wetted thoroughly. The clay pebbles are especially dusty so they need to be rinsed extensively before use. Two disadvantages of the clay pebbles are that they are heavier and do not hold water as well as the perlite. They seem to hold sufficient water for my plants to be fine overnight when I do not run the irrigation system, however, in the event of a power outage I think I would have to manually water the clay pebble pots more frequently than the perlite to keep them moist. Before I bought all my supplies and started setting up my system I watched some YouTube videos, one of the most helpful was “How to Build a Bato Bucket System” by ZipGrow. Their system was designed for 8 buckets, but I started with only 4 to make sure it worked before I invested more money into a larger system. I did make a table big enough to expand to 8 if I wanted to and I have since expanded my system. I also looked at some commercial systems that are available to purchase to see what supplies they came with to figure out what size water and air pumps, tubing, air stones, etc. I should purchase. Setting Up Your Hydroponic SystemI ended up setting up my Bato bucket system very similarly to the YouTube video but instead of one long system, made it to fit on a 4x4 foot table instead of a long 2x10 foot table. I also used drip stakes, instead of drip emitters because I like to push the stakes into the media to help hold them in place. For a Bato bucket system, you will need a nutrient reservoir unless you wish to manually water and drain the nutrient solution yourself. You can purchase reservoirs that are made specifically for hydroponics, but they are very expensive, which is why we cut a 55-gallon drum in half to use as our reservoir. Whatever you choose, make sure it is made of food-grade plastic and is opaque, or paint the outside to block light. Everything in hydroponics should be opaque to limit the growth of algae. You will also need the Bato buckets with elbows for drainage. I purchased these but many people have turned 5-gallon buckets into Bato buckets. PVC pipe that is 1.5” in diameter is needed for the drainage system (you need 10 feet if you want to have 8 buckets) plus an end cap for one end and an elbow for the drainage end. We ended up needing 2 end caps and 2 elbows once we expanded our system to two four-foot-long drainage tubes instead of one long one. One-half-inch tubing is used for the irrigation lines, plus a drain/stop valve for the end of the irrigation line if you want to be able to flush it. One-quarter inch tubing is used to run drip emitter stakes from the ½” irrigation tubing to the buckets, ½” clamps are used to clamp the irrigation tubing to the submersible pump and to clamp the drain/stop valve to the other end of the irrigation tubing. You also need a submersible pump to pump the nutrient solution to the plants as well as an air pump with air stones to keep the nutrient solution aerated. You can buy air pumps, air stones, and submersible pumps that are made specifically for hydroponics, or you can use ones that are designed for aquariums and ponds (just make sure they are food-safe). Zip ties are helpful to keep the air pump in place and we also used them to hold our irrigation tubing along a wooden rail in the middle of our two PVC drainage pipes. If you do one long pipe you can use 2-inch binder clips to hold the irrigation pipe along the backs of the Bato buckets, like in the YouTube video. I did not like this method because the irrigation tubing was so stiff it pulled the Bato buckets off the PVC drainage pipe and I ended up needing to put a large rock in the bottom of each bucket to hold them in place. In addition, a low table or bench is nice, so you don’t have to bend over so much as well as sufficient electrical outlets, a fan for air circulation, and a decent grow light. I used both 4-foot fluorescent fixtures with grow bulbs as well as a newer LED fixture. The LED light which was designed for hydroponics is much more powerful than the 4-foot fluorescent grow light, so it does not need to be as close to the plants and the plants grew much better on this half of my setup. I have since purchased a second LED grow light so I can have complete coverage of my 4’x4’ table. I use a 55-gallon drum cut in half as my nutrient reservoir. These are widely available in my area for free or cheap as most dairy farms buy solutions in them. We also cut the top off to use as a lid to help keep light out and help prevent evaporation. My reservoir holds up to about 30 gallons, but I usually have only 10 gallons of nutrient solution in it. When it drops by a gallon or two, I top it off until it is time to completely replace it. A rough rule of thumb is when you’ve had to top off your nutrient solution with the same amount as your total solution (in my case 10 gallons) over a certain period, then it is time to replace the solution. For example, if it takes 3 weeks before you add back a total of 10 gallons of solution, then you should replace the nutrient solution with fresh after 3 weeks. If this happens in one week then you need to replace it sooner, and you probably need a bigger reservoir. For me, I usually replace my nutrient solution with fresh, every 2-4 weeks depending on how many plants I have hooked up to the system and what stage of growth they are in. It is also a good idea to replace your solution regularly because, in addition to the depletion of nutrients, you may also want to tweak the different types of nutrients you use depending on the stage of growth. For example, you want to use a more dilute solution targeted toward vegetative growth when you first transplant your seedlings into your buckets. But later, when they start flowering you likely want to increase the nutrients and add more phosphorus-containing solution to increase flowering. In addition to the reservoir, we also made our lids for the Bato buckets as the ones I found online were flimsy. To make lids for our buckets we bought a 24”x36” sheet of HDPE food-safe black plastic and cut out lids to fit using tin snips. We cut them in half to make them easier to place around the plant and cut out holes with our drill press and Forstner bits for the plant stem plus the tubing for the drip stakes to fit through to deliver the nutrient solution. To set up the entire system, first, you need to set up your PVC drainage tubing along your table and drill holes into the top about every 1 foot for the drainage tube from the Bato bucket to fit into. We used 1.5” pipe clamps to hold the PVC pipe in place on the table. You need to cap the PVC on one end using PVC cement and place shims to lift one end of your table slightly or cut the legs on the drainage side of your table slightly shorter, so the nutrient solution drains out, instead of being stuck inside the PVC and potentially getting stagnant. You may need to get creative to make the drainage end of the PVC drain into your reservoir depending on what you are using. Since we set up a second drainage system attached to a single reservoir, we needed the 2 PVC drainage pipes to come together to drain back into the reservoir. If you have the space, it is easier to just make 1 longer PVC drainage pipe. Next, attach your larger irrigation tubing to your submersible pump and then run the tubing along the edge of your buckets. You need to either cap the end of the tubing or attach a shut-off valve so you can flush the tubing more easily. Then drill using 1/8” drill bits into the irrigation tube, preferably off to the side, and connect a small piece of ¼” tubing with a dripper stake at one end long enough to reach the center of the Bato bucket. The dripper stakes (I get mine from Drip Depot) come with adaptors to connect the ¼ tubing to your larger irrigation tubing, however, it is not unusual for these to leak slightly so you need to make sure it drips back into your bucket (this is easy if the tubing is attached to the side of the Bato bucket with 2” binder clips), or set up a system to catch the drips and return them to your bucket or reservoir if the tubing is not close to the buckets. I am currently just using aluminum foil to catch the drips but have recently purchased a food-grade glue to hopefully stop the leaking. I found the tubing to be very stiff so connecting it to the buckets was difficult and the binder clips were not always sufficient to keep it attached, plus if the buckets were light (only contained perlite) they sometimes moved due to the force of the tubing. Therefore, we switched to running the irrigation line down the center of the table and having the more flexible ¼” tubing running to each bucket. This way we can have 2 sets of buckets (4 on each side, 8 in total) on each side of the tubing and do not need to worry about trying to bend the ½” tubing to reach each Bato bucket. Last, you need to connect one end of ¼” tubing to your air pump and the other end to your air stones. I keep my nutrient solution aerating 24/7 but the submersible pump is on a timer to only run 3x per day. Remember, if your roots are submerged in water constantly, this will likely lead to root rot as the water will prevent the roots from receiving proper oxygenation. NutrientsOne big final question is what type and how concentrated your nutrient solution should be? I have been using the three General Hydroponics nutrient solutions with their CaliMagic and Floralious added in. I have also heard great things about the Masterblend dry mix which you combine with water. The advantage of General Hydroponics is you do not need to dissolve the nutrients, so it is faster to set up. The disadvantage is that it is more expensive, and I have had mold grow in the concentrated solutions which would not be a problem with long-term storage of dry nutrients. I have since started buying smaller bottles that I can use up more quickly before they get contaminated or expire. General Hydroponics has a great chart on its website for how many milliliters of each concentrated nutrient solution to add for each stage of growth per gallon of water. It also gives the ppm/EC value you should hit if you use those concentrations. Once you mix your solution you should double-check your pH (generally you want between 5.5-6.5 for tomatoes and peppers) and EC or TDS values. EC is electrical conductivity, a measure of any dissolved salts (nutrients) that affect the conductivity of your solution. Basically, the higher the EC, the more nutrients/salts are dissolved in the solution. EC is measured in mS/cm or millisiemens per centimeter. TDS is total dissolved solids and is measured in parts per million (ppm). I have an EC meter so I start off at 0.8-1 for seedlings and go up to 1.6-2.0 for full-size plants. I keep the lights on 18 hours per day when they are still growing but drop them down to 12 hours per day once fruiting begins. As far as what type of water to use, you should ideally have your water tested by a water laboratory to determine if it is good enough to use for hydroponics. I have yet to have mine tested but since I have softened water, I switched from sodium chloride to potassium chloride as a softener which is more expensive but better for plants. If you have water that is unacceptable for hydroponics, you can consider a reverse osmosis system or use distilled water. ConclusionHopefully, this post and the pictures help explain how to set up a Dutch Bucket system. If you have any questions, feel free to comment or send me a message! Make Your Own Seed TapesI love seed tapes for lots of vegetables that are directly sown, but I particularly love them for those that have small seeds, which makes them hard to sow thinly. If I sow the seed too thick, I must then spend hours every summer thinning my plants, or I end up with skinny, stunted plants. My favorite vegetable to use seed tapes for is carrots, as I have difficulty getting these seeds thin enough when sowing. I have even tried mixing the carrot seed with sand and using a shaker to spread the seed more evenly, but I still end up with carrots too close together. The convenience and speed of planting seed tapes are also nice as you can just lay them down and top them with soil (just don’t try it on a windy day). The big disadvantage to seed tapes is that they are much more expensive than just buying the seeds alone. Additionally, the varieties you can buy them in are limiting. My favorite part of gardening is trying lots of different varieties, but generally, you can only get very common varieties in tape form. Although making seed tapes is time-consuming, I find that I prefer to spend my time in the late winter making my seed tapes, when I am less busy rather than taking the time to thin plants in the summer, when I am much busier. Plus, most gardeners I know have a hard time thinning as they hate to kill any plant. I found two common methods online to DIY seed tapes. One method is to use school glue and the other is to use a flour-water mixture. I tried the flour-water mixture first and it worked so well that I have never bothered to try the glue method. You will need toilet paper (either one-ply or pull the two-ply apart so you use one sheet), toothpicks or a paintbrush, a small container to mix flour and water in until you get a runny paste, and a tape measure. The steps are simple: The flour mixture is dotted out at set intervals and a seed placed in each dot (left). The flour mixture is placed along the entire bottom/side edge of seed tape to seal (center). Seed tape is folded over to seal it and labeled with the variety (right).

Last, some lessons I learned using seed tapes:

Garden HuckleberriesAlthough I was unsure about garden huckleberries as they are a member of the nightshade family and are toxic until fully ripe, I decided to try growing them in the summer of 2018. I was pleasantly surprised by the plants as they were extremely easy to grow even with a particularly difficult growing season, which included an early-mid-summer drought and mid-summer hail. However, I only needed to harvest them one time at the end of the season which is much easier than many other berries that must be picked every day or two. However, once I made and tasted garden huckleberry preserves, I became a huge fan of the little berries. Garden huckleberries are not true huckleberries (genera Vaccinium and Gaylussacia) nor are they blueberries which are a type of huckleberry in the Vaccinium genus along with cranberries and bilberries. Instead, garden huckleberries are scientifically known as Solanum scabrum, a member of the nightshade family. Garden huckleberries are generally grown as annuals, and as such are one of the fastest ways of cultivating fruit. You do not need to wait 3-5 years to start harvesting fruit like many of the fruit trees and bushes that are more commonly available. Also, garden huckleberries do not take up tons of space in the garden but, do plan to allocate space similar to a tomato plant. Although nightshade plants can be very scary due to their well-known toxicity, many of our commonly grown crops are in the same nightshade family, including tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, tobacco, and potatoes. The biggest obstacle I had growing garden huckleberries was not being able to tell when they were fully ripe. I live in Wisconsin so our growing season (zone 4) is relatively short. Although garden huckleberries have only 75 days to maturity, I still found that many berries did not completely ripen before our first frost which is usually around the end of September, even though they had significantly more than 75 days to mature. I also started them from seed inside before transplanting at the end of May to give them even more time to mature. Many berries ripened to a black color throughout the summer and supposedly once they turn black and glossy, if you wait 2 more weeks, they will turn a dull black color indicating they are fully ripe and also no longer toxic. However, I found that the berries ripened at different times and it was too much work to try and pick out just the ripe ones. However, these are tough berries and generally do not get overripe so I decided to just let them on the plant until the fall. A mild frost is also supposed to enhance their flavor as well so this was another reason to wait. I finally harvested the night before our first “hard” frost. Literally, my family, including my in-laws, ran out to the garden in the dark using our car lights to see, and harvested all the berries before they froze. The hardest part of this whole process actually occurred after harvest. I spent a long time sorting ripe from unripe berries and making sure all the stems were removed. Some berries may look fully black but still have a tinge of green and if you cut them in half you will find the inside has not yet changed color. I threw out any berries that I could tell were obviously unripe. Since fall/early winter is crazy for my business I decided to just wash the berries and freeze them on a baking sheet before transferring them to freezer bags. I then forgot about them until January when the worst of the holiday rush was done. Once I had more time, I decided to try making garden huckleberry preserves. I am a huge fan of Tyrant Farms so I decided to use their recipe. These are not well-known berries and there is not a ton of information out there about them. However, one of the keys to these berries is that they must be cooked for their flavor to develop. If you eat them unripe, they are toxic, if you eat them ripe but raw, they should no longer be toxic but they really have no taste or maybe a slightly bitter taste. Trust me, you will not want to pop another one in your mouth. However, as I found out after tasting the cooked preserves, they taste absolutely delicious. The flavor is somewhat like blueberry jam. Some recipes recommend cooking them with baking soda to remove bitter flavors, but I found this was not necessary at all. Just make sure you are using fully ripe berries. A long cooking time is recommended as the skins are very tough, slightly leathery, and the berries can be hard to pop. Although I did follow the recipe and canned the preserves, the pH of the berries is unknown and the safer option is to make freezer jam instead of canning it. After making a batch of the preserves, I still had several pounds of berries remaining in the freezer so we decided to try making some garden huckleberry wine (yum!) which will be the topic of my next post once we get it bottled. Interview with Live to SustainWe were recently interviewed by Laura Weatherbee and Adam Cunningham from Live to Sustain. Adam and Laura are interested in living a more sustainable lifestyle and were curious about sustainability from a food perspective. In this interview Matt and I open up about our motivation for leaving the New York City area and what we have been up to since we bought our farm in Wisconsin. You can listen to the podcast interview here and also follow them on their website, as well as Facebook, and Instagram. Thanks for listening! Marisa |

Details

AuthorIn 2016, my family and I moved from the New York City area to small town Wisconsin. Our move, this website and blog (and our previous Etsy store) is the result of our desire over the past several years to simplify our lives, increase our quality of life, reconnect with nature, and enjoy a more self-sufficient life. I grew up as a country kid in central Pennsylvania working on my grandfather's fruit farm and as a corn "de-tassler" at a local seed farm. My background is in biology where my love of nature originated. I am a former research scientist and professor and have now transitioned to a part-time stay-at-home mom, self-employed tutor, and small business owner. Thank you for taking the time to check out my site. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed