Milkweeds and MonarchsThe monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is one of the most well-known butterflies but unfortunately, populations have been declining for years (1) though they are not yet at a critical level. Although other butterflies, such as the Karner blue, are at risk of becoming extinct and deserve more attention than they currently receive, the monarch is what I consider a “gateway” insect. Just like many people consider chickens the “gateway” animal on hobby farms (once you get chickens it often leads to acquiring other farm animals), the monarch is a butterfly that receives a lot of attention and leads people to understand the importance of saving other butterflies and insects that may not be as showy or pretty but still serve an important ecological niche. I will try to focus on other important insects in future blog posts but for this post, I will focus on monarchs. One of the reasons monarch butterflies may be harder to conserve than other species of insects is that they are migratory. Therefore, you need to focus on habitat conservation not just where they lay eggs and live as caterpillars but also where they overwinter as adults. Monarchs that live east of the Rocky Mountains migrate to Mexico (and sometimes the southern US) in the fall (2). Monarchs that live in the Pacific states often overwinter in California, but some also migrate to Mexico (2). The overwintered butterflies lay eggs in early spring where they spent the winter, those eggs hatch, and turn into adults, who then migrate back north into the United States and Canada (2). Most people are aware that the larvae (caterpillars) of monarch butterflies only eat milkweed. However, many people (myself included before a few years ago) may not realize that multiple milkweed species exist that can support monarch butterflies. Milkweeds belong to the Apocynaceae family, mostly the Asclepias genus, which contains over 200 species of milkweed plants, 73 of which are native to the United States (3). The Cynanchum, Sarcostemma, and Calotropis genera also contain some milkweed species. Milkweeds are named for their milky sap, which contains glycosides, which are toxic to humans and other species but not to monarchs. The toxins accumulate in the monarch making them unpalatable to predators. I grew up with common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) in Pennsylvania and it is also what primarily grows around my house in Wisconsin. I started butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) from seed two years ago and planted it in my front flower beds. Also, just FYI, a great place to buy native plants and seeds, either online or in person, is Prarie Moon Nursery. I also discovered last year we have swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) growing around our pond. Even though multiple milkweed species can support monarch caterpillars, is there one or more species that are the preferred food source? This is important for homeowners who want to help increase monarch butterfly populations but may not have the space to plant multiple species in their flower gardens. A research study of nine different milkweed species in midwestern Iowa by Pocius et al. discovered that the greatest number of monarch eggs were found on common milkweed and swamp milkweed (4). These milkweeds also had a high level of caterpillar survival. They also discovered that monarch caterpillars that hatched from eggs laid on honeyvine milkweed (Cynanchum laeve) and tall green milkweed (Asclepias hirtella) had the lowest survival rate (4) so these species would not be recommended to be planted. Another consideration for homeowners is how easily the milkweeds can be grown and transplanted. You can access the complete chart here, but other considerations include habitat, for example, swamp milkweed requires a wet location and common milkweed tends to spread aggressively via runners and therefore may not be the best choice for homeowners who want their milkweed to stay contained in a flower bed. A last consideration when planting milkweed is what species is native to your area. Ideally, you want to plant native species whenever possible as they will be the most beneficial to the insects in your area and the species that will grow the best in your area. To determine this, I suggest visiting The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) website (5) where you can find plant species based on a variety of criteria including genus. Here is the link to the Asclepias (milkweed) genus maps to help you determine which milkweed species are native to your area. As you can see common milkweed is native (dark green) to much of the eastern and midwestern United States extending into some southern states as well. If you do not already have native milkweeds growing in your gardens, I hope you will consider planting some to help the monarch butterfly recover in population. Many people also enjoy raising monarchs indoors and releasing them. Although this is a noble idea, this practice can cause the spread of a monarch parasite, Ophyrocystis elekrtoscirrha (OE) (5, 6). According to Morris et al., wild monarchs in Arizona had a 4% infection rate overall while farm-raised monarchs had a 29% rate (7). Although this protozoan (single-celled eukaryote) parasite occurs naturally outdoors, it can contaminate the equipment you use to raise the caterpillars and prevent them from developing properly into adults. Just like many diseases spread more easily among animals in captivity, the same can occur with monarchs raised indoors in close quarters. Additionally, data from Morris et al. in which monarch butterflies, both wild and farm-raised, were tagged and then recovered following migration suggests that farm-raised monarchs are less likely to successfully migrate (7). Farm-raised monarchs may be less fit, perhaps due to a loss of genetic diversity, than wild monarchs and thereby less likely to survive (6). Therefore, if you wish to make a difference for monarchs and other native insects, plant native vegetation and refrain from using pesticides as much as possible. References

0 Comments

My Favorite Seed CompaniesI buy from multiple seed companies because the various seeds all serve different purposes in my garden. I love open-pollinated/heirloom and hybrid seeds for different reasons. I love trying different varieties of seeds to see which grow best in my garden. I love different colors and tastes of different varieties of the same vegetables. Therefore, I buy from many seed companies. The following seed companies are the ones I buy from most frequently but are not listed in order of preference, I purchase from them depending on my needs at that time. I also try to order from companies that are based further north in the United States (my one exception is Baker Creek). I do this because the colder climate companies tend to have a greater seed selection that will perform well in my shorter growing season in central Wisconsin. If you are a Southern gardener, I would still recommend checking out the companies I like (most companies try to get a selection of seeds that perform well in different climates) but also look for some great seed companies that are further south and maybe even local to you. Lastly, I have generally had great germination with all of these seed companies, so I highly recommend them. Baker Creek Heirloom Seed CompanyI like Baker Creek because they only sell heirloom and open-pollinated varieties. These types of varieties are essential for anyone who wants to save seeds as they will always grow true if they do not cross-pollinate in your garden. I love saving tomato and pepper seeds, so Baker Creek is one of the main companies I buy them from. I also love trying different varieties of tomatoes and peppers and Baker Creek always has new and unusual varieties available. Baker Creek is also the last seed company I purchase from that still sends one or more free seed packets out with orders over a specific amount (3 free packets on a $65 order, 2 free packets on a $35 order, and 1 free pack on a $10 order) and they have free shipping on all seed orders. Also, their free catalog is pretty great but the larger one you can purchase is amazing! Fedco SeedsFedco is based out of Maine and so fits my criteria for a Northern climate seed company. They always have a large selection of shorter-season seed varieties which are perfect for my gardening zone. They also have a tree division from which I have purchased many bare-root fruit trees and bushes. Although Fedco offers heirloom and open-pollinated varieties they also offer hybrid seeds which I prefer when I am looking for disease resistance, bolt resistance, or another trait that can be harder to find in heirloom seeds. Although hybrid seeds can be expensive Fedco’s prices are reasonable, and they do have free shipping on orders over $50. Fedco also offers organic versions of many seeds if that is important. One last note about Fedco is that they are very open about where their seeds come from. They utilize a numbering system to show where their seeds are coming from such as small seed farmers (which includes Fedco staff), family-owned companies, companies not part of a larger conglomerate, and multinational companies that are or are not engaged in genetic engineering. This allows you to purchase seeds openly based on personal ethics. Fecdo has also recently decided to drop all Syngenta-owned seeds, even though many of them are popular hybrids, because Syngenta manufactures neonicotinoid insecticides which are known to negatively affect bees and other beneficial insect populations. In 2006 they also dropped all seeds from Seminis/Monsanto for similar ethical reasons relating to sustainability. This open-business practice is rare among seed companies, and probably most non-seed companies as well. Rohrer SeedsI like Rohrer Seeds for a variety of reasons, one of which is that they are based out of my home state of Pennsylvania and my family purchased their seeds when I was growing up. They have very reasonably priced seeds, you do have to pay for shipping, but their shipping is also very reasonably priced. Rohrer used to have a good selection of their branded seeds for 99 cents a packet. Those seeds have mostly increased to $1.99 a packet but that is still the cheapest per pack of all my favorite seed companies. Another reason I like Rohrer is that they sell seeds from other companies as well. So, I can get seeds from Lake Valley, Rene’s Garden, Livingston, Seed Savers Exchange, Baker Creek, and more, all in one location. The last reason I like Rohrer Seeds is that they have great customer service. I used to put in two separate orders, one for my vegetable seeds for my family garden and one for flower seeds that I would grow to sell on Etsy (back when I sold online). The workers at Rohrer would realize that the two orders were being shipped to the same place and ship them together and either refund me the shipping cost for one order or send free seed packets as an apology if they could not refund the shipping. I never expected to be refunded or given free seeds since I had to order separately due to my orders being personal versus business purchases. Although I no longer buy from them for business use, I still get many of my staple vegetable seeds from Rohrer. Johnny's Selected SeedsJohnny’s is another Maine-based company and probably the most expensive seed company I order from for both the cost of the seed packs as well as for shipping costs. So why do I still list Johnny’s as one of my favorite seed companies? Their seeds are of great quality and although they have some heirloom seeds available their hybrid selection is fantastic. If I have a problem with a disease in my garden (for example, one year I lost all my cucumber plants to downy mildew), Johhny’s is the first place I will look to see if disease-resistant varieties are available. Johnny’s also has a great selection of other gardening supplies including plant stakes, frost and shade covers, gardening tools, soil blockers, and more. They also occasionally hold informational webinars about gardening, usually about their specific varieties, which is a great opportunity to learn more about the growing conditions and properties of their seeds. MIgardenerMIgardener is based out of Michigan, another northern climate state. They are very similar to Baker Creek in that they only sell heirloom and open-pollinated seeds, but they are a smaller company with (maybe?) less selection although they have been growing steadily. Their seeds are very reasonably priced, and the company seems dedicated to keeping costs down for customers. All their seed packs are $2, and they have free shipping on orders $20 and more. They do not have a paper seed catalog which is one of the ways they can keep costs down and provide great prices for their companies. I buy many of my tomato and pepper seeds from MIgardener since I know they are open-pollinated, and I can easily save seeds from their varieties. ConclusionIf you have a seed company you love, please let me know in the comments below or send me an email. I always love trying out new seed companies! My Favorite Gardening Tools

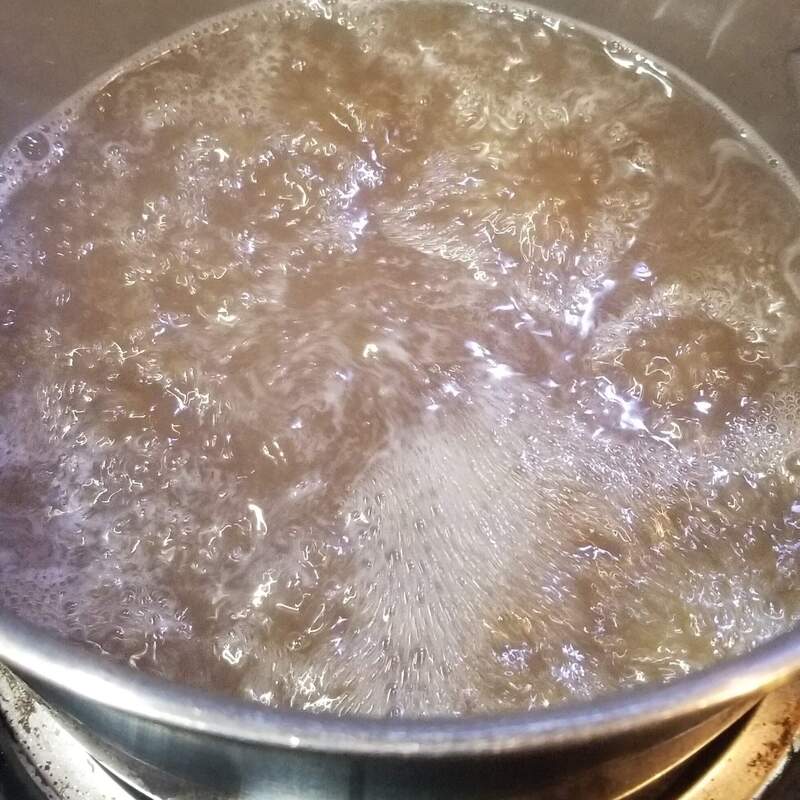

Maple SyrupingWe have been collecting maple (and occasionally birch) sap for about five years and boiling it to make syrup. This article is targeted to small, backyard syrup producers, collecting from ~2-12 taps. However, I will also discuss different methods to collect sap and make maple syrup if you wish to increase production. Why Make Maple Syrup?The truth is I do not eat maple syrup except for a taste once a year when we make it (I have difficulty regulating blood sugar). So why do I love to make syrup, even when I cannot enjoy the final product? The simple truth is that it is a fun, unique experience that occurs at a time of year when not too much else is going on. Maple syrup production occurs in early spring, and this is a time on our property when we have fewer tasks to do compared to late spring through fall. Collecting sap and boiling it down while you relax outside by a fire is a unique, almost magical experience that I highly recommend to anyone who has the chance. It is easy to buy real maple syrup, especially where I live because so many people make their own and sell extra. But real maple syrup is expensive and for good reasons. It is a time-consuming process to collect and boil down the sap, which generally has a 2-3% sugar content, into syrup which is 66-68% sugar. So, making maple syrup yourself may save money (if you do not count your time) depending on your setup and how you boil it down. If you have access to wood on your property you can boil it down for free (again, not counting your labor) but otherwise expect to pay for wood or propane to use as fuel. You can also make an evaporator relatively cheaply, if you are handy, or buy a large pot or flat evaporator pan to use over a wood or propane fire, to minimize expenses. However, unless you invest in a reverse osmosis system (more on that later) the one thing you cannot minimize is time. How Much Sap Do You Need?The general rule of thumb is that a 40:1 ratio of sap to syrup is needed if collected from sugar maples (other maples are closer to 50:1 and other trees can be tapped like birch and walnut but have even higher ratios). This means if you want to make a gallon of syrup each year you need to collect at least 40 gallons of sap. Larger producers now mostly use reverse osmosis systems first to eliminate as much water as possible and therefore increase sugar content before boiling the remaining sap with an evaporator to the final required sugar concentration for syrup. You can also collect sap from other trees to make syrup, including birch trees but the ratio is approximately 110:1, so you need over 100 gallons of birch sap to make a gallon of birch syrup. The syrup is also darker and more savory tasting than maple syrup, even with similar ending sugar content, and is often used as a glaze to cook salmon or pork. One advantage of birch trees though is that the sap tends to run after maple so by the time you are done collecting maple sap you can remove your taps and re-use them on any appropriately sized birch trees you may have. Walnut trees (Juglans), including black walnut, butternut, English walnut, and others can also be used. We have made birch syrup for a couple of years but prefer maple. We also have some black walnut trees on our property but have not tapped them as they are still too small. The color of almost done maple syrup (left) is much lighter than birch syrup (right). Timing MattersMaple syrup is always made in spring because that is when the sap starts running in trees. During the summer, trees conduct photosynthesis in their leaves. Photosynthesis is the process whereby trees and other plants take light energy and convert it to sugar. They use the energy from the sun plus carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and convert the carbon dioxide to organic sugars. In the process, they also release oxygen, which is very lucky for us! The tree uses the sugar to grow but extra sugar is pumped down from the leaves into the roots for storage over winter. The following spring when the days warm up, the sap starts running. The roots take up water from the ground and move it up the tree, taking all that stored sugar with it. Sugar is the energy source that the trees use to bud out and grow leaves that spring. Once temperatures start warming up to ~40°F during the day but still dipping below freezing at night, the sap will start running. In central Wisconsin, this is usually March into early April. This year (2024), however, we had a huge warm-up in the first couple weeks of February and again later in February, and many people decided to tap early (this is the earliest we have ever collected sap and made syrup). The season can be as short as a couple of weeks or as long as a month or more, but when the days and nights start getting too warm, the sap can go bad in the heat, and it also gets bitter. Usually, when the maple tree buds start swelling, this is a sign you should pull your taps. Supplies and EquipmentTrees – If you want to make maple syrup you need maple trees. Any larger maple tree works but sugar maples have the highest starting concentration of sugar in their sap. We have mostly red maples and silver maples on our property and measurements with a refractometer show a concentration of about 2% sugar in the sap. This can vary from tree to tree, even within the same species, and the beginning versus the end of the sap season. Generally, you want your trees to be at least 10 inches in diameter at 4-5 feet above the ground. You can put in 2 taps if your tree is over 20 inches in diameter. (1) I see many people putting in multiple taps in trees that probably should not have more than one, I prefer to put the health of the tree first. There are other trees that you can tap for syrup, but maple, birch, and walnut species appear to be the top three most tapped trees. Drill – You will need a drill, preferably battery-powered unless you are only tapping trees close to an electrical source. Some people even use hand drills, but I would not recommend this unless you are only tapping a few trees or have younger people to help drill. We use a 5/16th drill bit because our spiles are 5/16th in size. They also come in 7/16th and 3/16th inch sizes. Spiles/Spouts/Taps, Tubing, and Bags/Buckets – You will need tubing that fits your spile size. This year we switched from collecting sap in bags to using longer tubing into 5-gallon buckets. We have yet to tap more than a dozen trees so we can easily collect our sap by hand but if we ever expand, we will try using gravity flow to funnel the sap from multiple trees into one or more larger collection vessels. Most of our land is flat so this is probably only an option for a small section of our woods behind our house which only has about 8 tappable trees. Many commercial operations use a vacuum system to collect more sap and it does not require gravity to keep the sap flowing into a large collection bucket. If you are collecting sap in the bags or buckets that hang on the tree you only need a short, 1–2-foot, piece of tubing for each tap, or if you can hang your bag/bucket on the spile you do not need tubing at all. This year we started collecting sap in food-grade five-gallon buckets with a lid that we drilled a hole into to insert the tubing. Because we place the buckets on the ground, and you usually drill tap holes a few feet up this method requires longer-length tubing, but it is easier to collect and keeps more debris out of the sap. Although more expensive, the buckets also reduce plastic waste because they are more reusable than plastic bags and easier to clean out between collections. We use plastic spiles, but you can also find more durable metal ones. We now buy tubing in bulk from a local maple syrup supply company (The Maple Dude) and have found that the tubing comes in rigid or semi-rigid types. We much prefer the semi-rigid as it is easier to get over the end of the spiles. Tubing (5/16") can be bought in bulk (left), spiles, also known as spouts and taps (center) come in plastic (pictured) or metal, and water storage jugs (right) are a great way to store smaller amounts (6 gallons) of sap. Rubber Mallet – We use a rubber mallet to pound the spiles into the trees after drilling. 70% Isopropyl Alcohol – We use 70% isopropanol to sterilize the drill bit before drilling and the spiles before inserting them into the tree. Thermos of Hot Water – A thermos of hot water is helpful to warm up the end of the tubing before you place it over the spile. This is especially useful if you have rigid tubing! Even with the hot water we sometimes have difficulty fitting the rigid tubing over the spile. Rope and Bungee Cords – These can be helpful if you are using the collection bags, we have had the wind pull the bags far enough away that the tubing falls out. We usually tie the bags to a tree branch if possible, instead of hanging it off the spile for more security and then wrapping a bungee around the top of the bag and the tree to help hold it in place. Filters – You will likely want at least 2 different kinds of filters. A sap filter is used after collecting the sap to remove any sticks, insects, or bark debris from the sap. A finishing filter (often with a pre-filter inserted) is used for a final filter of the syrup at the end of the boil. Evaporator/Pan or Large Pot - Last year we invested in a StarCat wood-fired evaporator (the smallest one they make) from Smoky Lake Maple Products that has saved us lots of time! Before the StarCat we used a 10-gallon brewing pot on a propane burner which worked well but took 12-14 hours to boil down a 10-gallon batch plus the added expense of buying propane. Fuel – We used propane for several years but as prices and our sap collection volume increased, we decided to invest in a wood-fired evaporator since we have lots of hardwood available on our property. We now use wood to boil the sap until the volume gets too low for the evaporator. We then transfer the sap to a pot over the propane burner until it is just about done, then finish boiling it on the stove in our house. Reverse Osmosis System – Another improvement to increase efficiency is to invest in a reverse osmosis system to save time boiling the sap. Small backyard syrup producers can buy reverse osmosis systems that can concentrate sap from about 2% sugar to 4%. This might not seem like a huge difference, but it doubles the sugar concentration which should decrease the boiling time by half. If you have 100 gallons of 2% sugar the RO system can get it down to 50 gallons of 4% sugar. So instead of a 24-hour boil (or more), you might be able to get it done in a more reasonable 12-hour day. The wood-fired StarCat Evaporator (left and center) is much more efficient than our old method of using a 10-gallon brew pot on a propane burner (right). How to Tap Trees and Make Maple Syrup

ConclusionIf you get the chance to collect sap and make syrup or even help with someone else’s collection and boil, I highly recommend it. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me. References

The Basics of Seed StartingI started growing my vegetable plants from seed rather than buying seedlings from big box stores or local greenhouses for several reasons. First, I love working with soil and plants so by starting seeds I get to start gardening (albeit indoors) earlier than I would if I bought seedlings. Second, I have a very large garden, so I save money by buying seeds and starting them rather than buying plants. Lastly, one of my favorite parts of having a garden is to try many different varieties of vegetables, especially tomatoes and peppers. If I buy my seedlings from big box stores or even independent greenhouses my selection is much more limited than if I buy seeds and start my own. Before I get into the supplies you will need to start seeds let's discuss timing. I see this question asked all the time in my online gardening groups and there is not a simple answer. The easiest way to get a rough idea of when to start your seeds is to first figure out your average last frost date in spring. There are lots of different websites and I would recommend checking several, but this one has worked well for me and gives dates close to many other sites. Once you enter your zip code, look for the 50% chance of last frost at 32°F, which for me is mid-May. Remember, this is an average and in any given year the date could easily fluctuate by a week or two. Realistically, I generally do not get my warm season crops, both directly sowed seeds and transplants, planted until the soil warms up more which is usually the first week of June for me. Once you know your average last frost date count back, however many weeks is recommended (check your seed packet or do an online search), to figure out when you need to start seeds. For slow-growing and slow-germinating seeds like onions, celery, artichokes, and some herbs like parsley I start seeds 8-10 weeks before my last average frost date. For many cold crops like cabbage, kale, broccoli, and cauliflower I plant 7-8 weeks ahead. For peppers which can take weeks to germinate (especially the super hots), even with a heat mat, I start about 7-8 weeks before my average frost date, but I generally plant them out 2 weeks after my last frost date since peppers do not like the cold. Lastly, for tomatoes, which germinate and grow more quickly than peppers I start later, about 4 weeks before my last frost date. Again, I usually wait a week or 2 after my last frost date to transplant to make sure the air temperature and soil temperature are warm enough. The reason seed starting dates is not an exact science is because even knowing your average last frost date you may live in an area with a microclimate that is either warmer or cooler than average. You can start tracking your temperatures where you live, but that would take years to get good data or learn to enjoy a little trial and error. As mentioned above the actual last frost date can vary because it is based on an average. Also, the temperature in which you are growing makes a difference. I found that when I started putting my seedlings into a greenhouse for a couple of weeks before I planted them, they grew much faster than when I had them growing in my cooler basement. So, I had to adjust my dates and start my seeds later to account for faster growth. The best resources I have found to help you calculate dates are from Johnny’s Selected Seeds which has SO MANY freely available calculators and tools, some of which are downloadable. My favorite tools are their seed-starting date calculator for seedlings and their fall-harvest planting calculator. They also have a succession-planting calculator which I have never used it as I do not have much time to replant most seeds due to my short growing season. Once you have your seeds organized and dates figured out it is time to get all the supplies you need. Some of these supplies are optional so buy what you can depending on your budget. I also recommend starting just a few different types of seeds in your first year and if it goes well increase the number you grow in the years after if you want. You do not want to end up overwhelmed or with a bunch of leggy, or even worse dead seedlings because things went wrong (trust me I’ve been there). Seedlings in 6-cell pots with a fan blowing (middle) to strengthen them and help avoid damping-off. SuppliesBefore you start seeds, you need to stock up on a few supplies.

From left to right, onion seedlings under 4 foot LED 5000K lights, lettuce seedlings potted up into 3.5 inch square pots, and endive and pac choi recently transplanted into a raised bed. ConclusionI love starting my own seeds and hopefully you will too. Just remember if it does not work out great your first time, try again! My first time I started seeds I went on vacation and the person who was checking in on my seedlings overwatered them because she thought they were dying. It turns out they were dying because I had problems with damping-off (this was not her fault, some had started dying before I even left for vacataion). Unfortunately, watering even more makes damping-off worse so I lost about half or more of my seedlings that year. I have since learned that less water is usually better and I also try to time my vacations until after the majority of my plants are in the ground! Good luck and feel free to contact me with any questions! |

Details

AuthorIn 2016, my family and I moved from the New York City area to small town Wisconsin. Our move, this website and blog (and our previous Etsy store) is the result of our desire over the past several years to simplify our lives, increase our quality of life, reconnect with nature, and enjoy a more self-sufficient life. I grew up as a country kid in central Pennsylvania working on my grandfather's fruit farm and as a corn "de-tassler" at a local seed farm. My background is in biology where my love of nature originated. I am a former research scientist and professor and have now transitioned to a part-time stay-at-home mom, self-employed tutor, and small business owner. Thank you for taking the time to check out my site. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed